Introduction

Access to information is not a problem for most university students. What may be a problem, however, is understanding what sources of information are appropriate to use as a university student of the sciences. In ecology, written arguments must be supported by a body of empirical facts or data. The majority of your work in this course will be completing your field-based research project, and much of that effort will be presenting a formal written report of your observations and conclusions. Like the peer-reviewed literature on which your research paper will be modeled, every statement in your paper must either be a logical conclusion from previous statements or supported by reference to original observations supporting that statement (either made by yourself, or more typically, made by others). The ability to discriminate among different sources of information is a critical skill that you must learn. Surprisingly, this is more difficult than it sounds. This tutorial is designed to help you with that task.

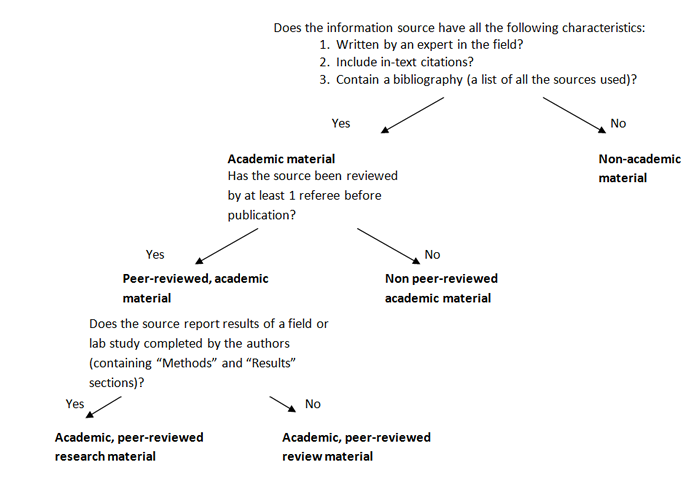

We will classify information sources into four different categories:

- non-academic material

- academic material that is not peer-reviewed

- academic peer-reviewed review material

- academic peer-reviewed research material

Discriminating among these different types of sources is not based on the source’s form (i.e., book, webpage, journal article, or government publication), but on its content and the process the information underwent as it was being published. This figure provides a flow chart that distinguishes among possible sources of information.

Flow chart for discriminating among different sources of information.

Introduction

For the purpose of this course, academic sources are distinguished by three characteristics: (1) they are written by an expert in the field, (2) they include “in-text citations,” and (3) they contain a bibliography (which may be labeled as “Bibliography,” “Literature Cited,” or “References”). Any source of information (such as encyclopedias, books, book chapters, newspapers, magazines and websites) that lacks one or more of the three characteristics is considered non-academic. Requiring the author to be an “expert” places a high standard on the source. It is difficult to define an expert; however, for the purposes of this course, an expert will be characterized as someone who is affiliated with an institution (academic, governmental, or non-profit), is either paid to conduct the research or has published in the field previously. If a source lacks “in-text citations,” it is impossible to track the authenticity of each statement the author makes. Likewise, if the material lacks a bibliography, it is difficult to find the original references the author used to build his or her argument. Therefore, it is inappropriate to use non-academic sources as a reference for your own research papers. This doesn’t mean that all non-academic sources are useless to consult when researching a biological question. Many non-academic sources of information, like encyclopedias, books, or Wikipedia entries, may provide a good introduction to your topic and may provide a bibliography that could list academic sources.

Academic sources of information include both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed materials. Non-peer-reviewed academic sources are published without the material undergoing a rigorous process of being critiqued by other experts in the field. Written material of this type may be an excellent source of information, as it tends to be easier to read than peer-reviewed information sources, yet still be authoritative. Note, however, that it may not be easy to determine whether or not a source qualifies as academic. For instance, if a third-year biology student posts a term-paper on the web without providing any information about him or herself, it may be difficult to determine if the author is an expert. Library books related in some way to your topic often fall into this category.

Before publication, peer-reviewed academic sources have been evaluated and critiqued by other experts in the field. In this process, authors submit their material (usually articles are submitted to a scientific journal, but some book chapters and other material may be peer-reviewed) and the editor of the publication asks one to three experts in the particular field of research (known as referees) to critique the submitted work. Ultimately, the editor assesses the referees’ comments and decides whether the work warrants publication.

Types of Peer Reviewed Articles

There are two types of peer-reviewed articles:

- Academic, peer-reviewed research articles are written to report the results of studies which have been undertaken by researchers to try and answer a specific question(s), and include detailed methods and results from a particular experiment(s).

- Academic peer-reviewed review articles typically examine several different lines of research (i.e., discuss several research articles) on a particular topic and summarize, synthesize, and/or critique the results of this research.

Peer-reviewed materials (both research and review) are most commonly available as articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. A variety of these may be found in “hard copy” in the TRU Library. Many of these, as well as thousands of others, can be also accessed through the Library website (http://www.tru.ca/library/article.html). In terms of an information source for biology students, peer-reviewed articles have the highest credibility and authority. They may, however, be difficult to understand if you are just beginning to learn about a subject.

Examples of information sources

Example 1

Our first example is an, apparently, peer-reviewed article from a scholarly journal:

Bratman, G. N., P. J. Hamilton, and G. C. Daily. 2012. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1249:118-136.

[You can access the full text of this article from https://www.tru.ca/library.html by using the Journals tab to search.]

Let us consider the first four questions from the flow chart:

Examples of information sources

Example 2

The next example is a government technical document:

Michelle D. Staudinger, Nancy B. Grimm, Amanda Staudt, Shawn L. Carter, F. Stuart Chapin III, Peter Kareiva, Mary Ruckelshaus, Bruce A. Stein. 2012. Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity, Ecosystems, and Ecosystem Services: Technical Input to the 2013 National Climate Assessment. Cooperative Report to the 2013 National Climate Assessment. 296 p. Available at:http://assessment.globalchange.gov

[Document available at http://crownmanagers.org/storage/Biodiversity-Ecosystems-and-Ecosystem-Services-Technical-Input.pdf.]

Examples of information sources

Example 3

The last two examples are somewhat atypical: most journal articles are, in fact, peer-reviewed, while most government documents are not. This highlights the importance of determining, for yourself, the nature of your sources.

Another scholarly article:

Matthews, J. W., A. L. Peralta, D. N. Flanagan, P. M. Baldwin, A. Soni, A. D. Kent, and A. G. Endress. 2009. Relative influence of landscape vs. local factors on plant community assembly in restored wetlands. Ecological Applications 19:2108–2123.

[You can access the full text of this article from https://www.tru.ca/library.html by using the Journals tab to search.]

Examples of information sources

Example 4

Finally, a popular web destination for all seekers-after-knowledge:

A Wikipedia search for “ecosystem services.”

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecosystem_services]

1. Was the information source written by experts in the field?

Wikipedia entries, while providing much wonderful information, do not provide easily assessable information on authorship. And although the iterative editing process acts as a safeguard of the quality of the information presented, Wikipedia’s open access policy means that anyone can contribute to an entry, regardless of expertise. The answer to the above question is therefore No. This source is non-academic material. See http://libguides.tru.ca/evaluateweb for helpful criteria for evaluating the reliability of websites.